“triggers” and “bullets”: assessing “White Fragility” in a diversity initiative

“triggers” and “bullets”: assessing “White Fragility” in a diversity initiative

By: Justin Laing | September 21, 2021 | Antiracism, Diversity Inclusion Equity, Research

Not too long ago, I led an evaluation of an arts diversity initiative in which a funder was evaluating the impact of a multi-year initiative intended to help arts organizations increase their level of diversity, equity, and inclusion. All but one of the organizations was predominantly White American led. I collaborated with the participants to define key questions, data collection, and data interpretation and applied Critical Race/Critical Pedagogy/socialist frameworks. This post will share the methodology and reflections on this experience.

The participatory evaluation extended over the course of about 18 months and had a number of dimensions, but this post is about applying the framework of “White Fragility” in evaluating a diversity program. As I explain below, participants were interested in understanding the role “White Fragility” had played in the Initiative and so, my intention was to make Whiteness a particular evaluand and develop tools with which to engage and challenge it.

To begin, by “Critical Race/Critical Pedagogy/socialist frameworks”, I mean to say:

Definition of terms

- I approached the evaluation with the critical race assumption that racism is the normative American condition and thus would operate in the process to advantage people of European descent, particularly those of the capital class, and disadvantage non-European people, particularly people visibly of African descent. So, I would need to be an active participant in disrupting that process and, even then, White led institutions would still only advance Black people’s agenda to the extent that their mutual interests converged i.e. interest convergence.

- In keeping with the critical pedagogy frame, I did not employ a “logical positivist” model, or the idea that there is some intrinsic, non-political, objective truth that exists separate from the learner. Instead, I used an interview-based evaluation in which participants co-designed, with the sponsor, the evaluation goals, conducted interviews of one another, and then played a role in interpreting the data at the project’s end. The hope was that in using this approach, the data would first be seen by participants, rather than first interpreted through the lens of the evaluator and there would be a collective benefit.

- Building off of ideas of Cedric Robinson (Black Marxism),I worked under the assumption that race and capitalism are intrinsically related, so an effort to disrupt racism must also disrupt the norm of labor exploitation. In this process, I advocated for and the sponsor agreed to pay for the participants’ labor as data collectors and interpreters. We imagined the total labor involved and budgeted $100 for each hour it would cost participants. This was intended to be a form of socialist valuing of labor in the way it pushed back against capital’s expectation that so much labor in evaluation is invisibilized and made free.

Process

In the project’s first phase, I facilitated two sessions with participants in which the evaluation goals were developed alongside those of the sponsor. During that part of the process, one of the goals offered by a person of color was to understand the role that “White Fragility” played in disrupting the diversity projects of this initiative. In keeping with the Critical Race approach to prioritize the unique voice of people of color, it felt important to facilitate this becoming one of the overall goals of the evaluation. This decision, in turn, would have a big impact on data collection and interpretation, and I am grateful for the courage shown by that participant to offer this viewpoint.

In wanting to support the group with tools based on an understanding of the concept of “White Fragility,” the first step was to understand the term and so I read Robin DiAngelo’s book “White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard For White People To Talk About Racism”. DeAngelo breaks White Fragility into eleven “triggers” and four “bullets” , each with an accompanying explanation of why it is “triggering”. “Triggering” was offered by a White participant and, so I use that language and complement it with “bullets” to round out the analogy and in keeping with Paulo Friere’s frame in Pedagogy of the Oppressed that violence takes on many forms beyond physical violence.

Triggers:

- Suggesting that a White person’s viewpoint comes from a racialized frame of reference (challenge to objectivity).

- Suggesting that a person being a part of one racial group or another has a significant impact on their life outcomes and experiences (challenge to individualism).

- Choosing not to protect White people’s feelings about race (challenge to White racial expectations and the need for, or entitlement to, racial comfort).

- Being presented with a Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) person in a position of leadership (challenge to White authority).

- A White person receiving feedback that their behavior had racist impact (challenge to White racial innocence).

- Being presented with information about other racial groups, for example, movies in which BIPOC drive action but are not in stereotypical roles or multicultural education (challenge to White centrality).

- BIPOC people talking directly about their own racial experience (challenge to White taboos against talking openly about race).

- A White person disagreeing with another White person’s racial beliefs (challenge to White solidarity).

- An acknowledgment that access is unequal between White people and other “racial” groups (challenge to meritocracy).

- People of color being unwilling to tell their stories or answer questions about their racial experiences (challenge to the expectation that people of color will serve us i.e. White people).

- Suggesting that White people do not represent or speak for all of humanity (challenge to universalism).

Bullets

- Sounding incoherent in discussions of race

- Expressing anger, fear or guilt in discussions of race.

- Saying that they or another White person are being attacked or that it feels like an attack in a conversation about racism.

- Angrily arguing, silence or leaving the discussion.

Being able to define the term, I created a survey asking people to what extent they had experienced or witnessed this series of phenomena. The survey itself triggered its own response which included White participants angrily arguing that they could not see the relevance of taking the survey or dismissing the concept of White Fragility altogether. Engaging these responses from White participants and sponsors consumed a lot of time but it was also informative to see what it was like to apply these kinds of frameworks in an evaluation context. Concerned that including these responses as actual data would only repeat the cycle of White Fragility once the evaluation was complete, I did not use the responses as data points. However, as the evaluation was a part of the DEI program, White Fragility evidenced in discussing White Fragility was itself disruptive. Another informal data point was that despite participating in this multi-year DEI program, the majority White group did not engage these participants as they demonstrated the specific characteristics of White Fragility.

After the interviews were completed by the participants, I completed another round of interviews and then reviewed post-DEI workshop surveys as well as the DEI training materials. Using a computer-assisted coding software, I “coded” interviews conducted by the participants as well as surveys filled out by program participants. By “coding” I mean every time I saw an occurrence of one of the triggers or bullets I labeled it so that I could keep track of how many times and where it was occurring in the data. As participants went through equity training as a part of the program that included frames of “intersectionality” and “white supremacy culture”, I also created 15 codes to mark when elements of Critical Race Theory were either invoked or supported as well as another 14 codes for White Supremacy Culture.

In keeping with the participatory nature of the evaluation, in the first round participants interviewed one another as they explored each organization’s theory of change. Afterwhich, I completed a second round of interviews and reviewed post DEI workshop surveys to gain a better understanding of the participants’ experience in the DEI workshops referenced above.

I used ATLAS.ti, to “code” interviews conducted by the participants as well as surveys filled out by program participants to explore the efficacy of the organizations’ and funder’s theory of change.. In the case of White Fragility, every time I saw an occurrence of one of the triggers or bullets I labeled it so that I could keep track of how many times and where it was occurring in the data. As participants went through equity training as a part of the program that included frames of “intersectionality” and “white supremacy culture”, I also created 15 codes to mark when elements of Critical Race Theory were either invoked or supported as well as another 14 codes for White Supremacy Culture.

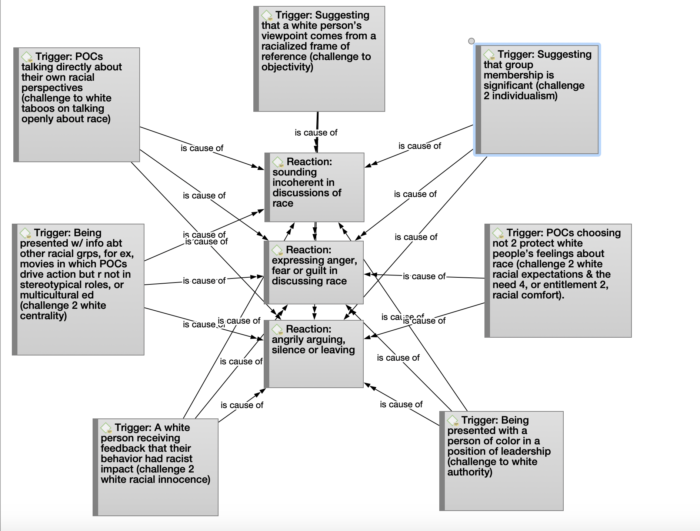

Upon completion of the coding, I created a visualization of triggers and bullets. What became clear was the near-impossible balancing act of remaining employed by White institutions, while also expressing their lived experience as BIPOC people, in ways that challenged the White Supremacist Culture. I tried to represent this reality in the network map generated by the coding program.

A couple of takeaways from this map. First, the term “White Fragility” is a weak concept because by its own definition, it is a strategy of aggression in an effort to maintain racism but suggests that it is the White person who is at risk. Thus, my use of “triggers” and “bullets” is an effort to reframe the concept as one of violence. D’Angelo says “White Fragility” would be better named as “bullying”. However, even “bullying” encourages us to see the issue in individual, “on the playground” terms, rather than serving as an important cog in institutional and systemic racism. However, the behaviors associated with “White Fragility” do point out the conceptual problems of the “racism without racists” framework that we often use to describe systemic racism. In this model of systemic racism, systems created years ago now just operate delivering racist outcomes despite our better intentions. The map above explains the innate conflict of interest of White people in operating and even trying to reform this system because if the DEI program was fully successful, as a group, they would share much more authority, jobs and influence with their BIPOC counterparts.

Reflections

The process culminated with my interpreting the data and offering recommendations. These recommendations were not developed in a collective manner, but rather were largely my offerings. In this, there are a few issues:

(1) the participatory process is quite labor-intensive, and when it is placed on nonprofit workers who are already overworked, it can feel burdensome. This is a conversation that should be had at the outset.

(2) As Black radical frames are not the dominant frame, particularly in a White-dominated space, interest convergence would say that there will not be recommendations that increase the power of Black artists and cultural workers anytime soon. In such cases, democratic participation, collective learning, Whiteness and Black power operate in conflict. This is also a consideration that should be explored at the outset. How will it be decided if minoritized voices raise criticisms of Whiteness i.e. who will be the decider of whether these make it to the public?

(3) Even conducting this evaluation was named as threatening for POC participants because it essentially forced a conversation that could then put POC participants in danger from White responses or maybe even their own reliving of trauma, so evaluators and sponsors need to take care of protections even in pursuing these questions.

Finally, this experience was another confirmation that without a broad power building strategy led by Black artists and cultural workers, the “White Bullying” that sits as an unnamed obstacle in DEI agendas will likely continue to be an effective tactic in protecting the benefits professional class White people receive from the rulling class in exchange for not challenging the relations of power between those two groups.